The Tambo River flows through the department of Moquegua in southern Peru. Starting high in peaks and Altiplano of Puno, the river crashes through a deep canyon in the volcano-infested region just south of Arequipa.

In March of 1998, with the heavy El Niño rains punishing the Northern coast of Peru, several of us set off to investigate the Tambo, which was supposedly in a partial rain shadow, which was at the time less affected by the torrential floods occurring a few 100 kms to the north. We drove with a friend from Arequipa to the where the Tambo River crosses under the Pan-American highway some 4 hours south of Arequipa. Although it was nighttime and therefore dark, we could see the flow and estimated it to be 1000 CFS. We speculated on what the river would be like 120 km upstream in the deep canyons of the Andean Cordillera. After viewing topographic maps we decided to drive to the upper portion of the river and put in somewhere below Volcan Ubinas. Our intent was to enter the canyon and reach a bridge crossing near the village of Quinistaquillas some 50 km downstream at 1500 meters of elevation. We estimated 6 days and Gian Marco’s father agreed to meet us there with the vehicle.

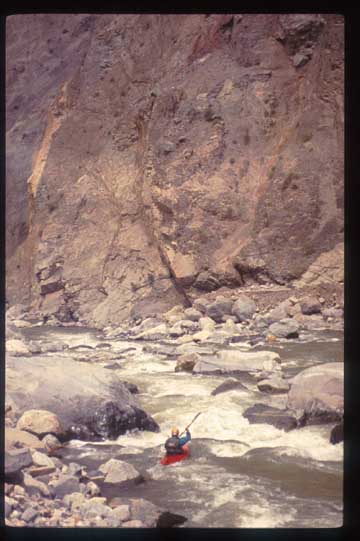

Gian Marco Vellutino Upper Tambo

On the trip we had John Foss, Andreas Fischer (Germany), myself, and Two Peruvians: Gian Marco Velutino and Jose Francisco (Cachemere) Giraldo. We drove in Gian Marco’s van along with his wife, son, and father up to the Altiplano and Laguna Salinas. Laguna Salinas is home to thousands of Parihuanas (pink Flamingos) whose colors gave rise to the Peruvian flag. We followed the road to Juliaca and turned off to follow a tract to the village of Ubinas. This village, which is situated at 3200 meters, is located on the backside of Volcan Ubinas (5625 meters), whose recent eruptions from 1936-1939 still bring memories of respect to the elders of the village. From Ubinas there is a road that winds its way down to the river. We camped at a village called Huatauga where the road disappeared at a Quebrada Para. A Huayco (landslide) had taken out the road in February.

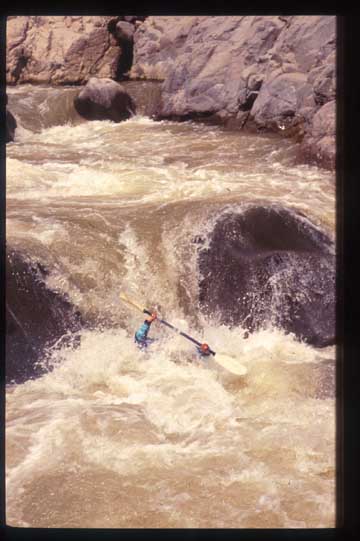

Cachemere Upper tambo

It was only an hour carry with our boats to the river. We put on at the confluence of the now dry Rio Para and Tambo, the latter whose flow contained 600 CFS. A few km downstream we reached hot springs called Ojo Mela. After a soak we continued downstream making camp at 2350 meters across from the Pampa De Candahua. The whitewater on the river was mostly class 3-4.

In the morning we reached the swinging bridge one km below camp. The bridge connects the villages of Candahua and Cacahuara. From here the river turned to class 5 and continued for next few hours until we reached what the locals call “Puente De Diablo”. This 6 km stretch dropped 150 meters for an average drop of 25 m/km. Here the river enters a vertical canyon with a right wall formed by Volcan Huaynaputina (4806 meters) and a left wall formed by Cerro Aromayo (4000 meters). The entry rapid into the vertical walled chasm is a 6-meter falls. We got out on river right to scout the canyon. Three of us began to climb the nearly vertical right wall with hopes that upon reaching the bench 200 meters above, we would be able to see into the canyon. The hike was viscous as the walls were covered with meters of volcanic ash from recent explosions. After several hours we reached the flat bench at the top of the canyon and to our amazement it began to rain, with blinding, torrential sheets of water. We abandoned the scout and quickly tried to return to the boats below. The rain caused the wall to slide behind us as we descended back to river level and we arrived in the dark to find the others cooking in a cave beside the river. The river was already starting to rise and we carried boats and gear to the highest point we could reach and hung all the gear from ropes and carabineers. Being without tents, we all looked for shelter at a high level. Most of us found refuge under an overhanging cliff but to sleep we had to tie each other into the wall. Around midnight I woke up with the full moon in my eyes and a deafening roar in my ears. The rain had stopped but to my disbelief the river had surged to an estimated 50 times its previous volume and was within inches of reaching the shelf we were camped on (at what was 20 above the river.) I woke everyone up and we tried to get to higher ground. By 2:00 the river started dropping and by sunrise it was down to a few thousand CFS. The boats were safe but we had lost the kitchen, water filter and most of our food. After watching the river for a while we realized that the level had stabilized at a few thousand CFS and was no longer dropping. We all agreed to bail out. The question became HOW and to WHERE. Gian Marco and Andreas agreed to climb out of the canyon and head back upstream to look for nearest village. Cachemere, John and I would stay behind and try to get boats out of canyon and up to bench 200 vertical meters above. John was sick and not able to help so it took Cachemere and I 2 days to get the gear up to the bench. At this point Gian Marco and Andreas returned with news that they had found a village and that some people with burros would be arriving the next morning. Although out of the vertical gorge we still had to carry the boats up another 400 vertical meters to find the remnants of a trail to the village.

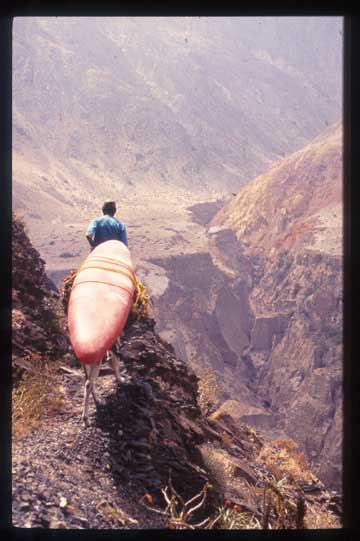

The next morning three burros and a mula showed up and we loaded the animals for the 6-8 km trail to Candahua. The trail was seldom used and was in terrible condition. We spent the whole day on the trail and at many times had to unload and carry over treacherous stretches and steep pitches. We arrived at a swinging bridge and we told by the animal’s owners that they could not help us carry gear the next day onto the next village of Matalaque (where the road reaches and there is bus service). The animals were needed in the fields to carry the Tuna (Prickly pears) harvest. We would have to wait one day for the animals to make the 15 km trek to Matalaque. Rather than hike one hour up to the village we chose to make camp on a wide beach above the swinging bridge. Once again we started to cook dinner and the rains came. Within minutes the river was raging and we were scrambling with our gear to get to higher ground. With the walls of the riverbed being vertical we had had to walk down the river corridor for a few hundred meters. The water, which started at ankle level, was chest high when we reached the safety of the swinging bridge. We all huddled on the bridge and were amazed at how fast the river was rising. Massive Huaycos could be heard crashing down the mountains all around us and sparks from falling stones were lighting the sky. As the rain subsided and the light improved I saw what looked like milk coming down the mountain across from us. With all our camping gear and clothing soaked we abandoned the boats and headed to the village of Candahua. The trail we followed had just been the source of my milky white vision, in that a massive debris flow had come down the mountain and inundated the trail. We reached the village and found the few inhabitants hiding outside of their homes. The village headman let us sleep in his shed where we were packed liked sardines on the floor with chickens, rats and guinea pigs running all over us.

Hiking out on the huge Tambo Canyon

In the morning we learned that the storm, although short by my standards, had been the worst in 25 years. The trail we had just followed the day before no longer existed and the trail to Matalaque was impassable with animals. We tried to find people in the village to help carry our gear but no one was available. Gian Marco once again set off on foot for the town of Matalaque in an effort to find people to help with the boats and to use the radiophone to call his family and advise that we were okay. The rest of us set off on foot for Matalaque, carrying our gear only and abandoning the boats. The trail was in horrible condition and the progress was slow but at 5:30 PM we came across Gian Marco and a bunch of guys from Matalaque. Without gear they were able to run to Candahua and retrieve the boats. We arrived in Matalaque in the early evening and the boats showed up around midnight. Gian Marco explained that he had spoken with Arequipa by phone and had explained that we were okay. Apparently Gian Marco’s father had used a radiophone and had called Arequipa from the town of Omate (near our intended takeout). His father had arrived at the river and found no sign of us but was shocked to see several thousand CFS of brown churning water crashing over a 30 meter falls.

Being in Matalaque we thought we were home free and that a bus would be arriving in the morning to take us back to Arequipa. What we learned was sobering. The same storm had taken out the road from the pass down to Matalaque. We would have to carry our gear 800 vertical meters to a place called Nazcapa where the bus could reach. We decided to abandon the boats and organized for a horse to carry our gear to meet the bus. We started out at 3:00 AM and reached a descending truck and bus at 10:30 AM. On the bus was a group well stocked with Shovels and picks that were determined to reach Matalaque. Since the bus was retuning several of us jumped on to help with the road and to get our boats we had left behind.

Several hours later we reached town and retrieved our boats. The bus set off in the early evening to reach Arequipa. Somewhere near the pass but not quite to the point where our other friends were waiting, the axle sheared on the bus. The night air was viscous and we huddled together while waiting for the ascending truck, which arrived sometime after midnight. Our friends, who were waiting for our return did not have their bags with them and were freezing without spare clothing. The truck was packed with around 35 people and boxes of fruit. We crawled in and began a torturously slow, and incredibly cold, 14-hour journey over the Altiplano back to Arequipa.

Nine days after leaving Arequipa (with only two days on the river) we returned hungry and tired. The Tambo had definitely kicked our ass. Even if the big rains had not come and even if we had managed to portage the first canyon, we would still have had trouble with some of the remaining canyons. The topo maps indicated at least two more heinous canyons with severe constrictions on the way to Quinistaquillas and lots of gradient.

In retrospect I think it will be a while until someone completes this stretch of river and that a more reasonable, but still exciting 25 km stretch, will be from Lloque (3300 meter to Matalaque at 2500 meters)